Be a rocketship or leave a big crater

Your investors want you to either be massively successful or worthless.

531 words • 3 min read

If you raise venture capital, you’re committing to a path: you’re either going to be a rocketship or you’re going to leave a smoldering crater. There are rarely soft landings.

It’s critical that you understand this before you raise money.

Why does it work this way?

The model requires it

The venture capital model requires outsize returns.

As an example: your investor invests $1m in 100 companies. They expect 99 of them to fail, and one of them to become a megahit, turning that $1m into $500m or $1b, delivering a nice 5-10x outcome for the fund.

Said another way, a modest exit is a failure, not a success. A good outcome is turning $1m into $500m. Turning $1m into $2m seems like it should be a good thing, but it’s a bad outcome for the VC investor. (2 is a lot closer to 0 than it is to 500.)

Let’s say your startup is deciding between these two strategies:

Strategy A: 90% chance of doubling the company’s value, 10% chance of losing it all

Strategy B: 10% chance of 100x’ing the company’s value, 90% chance of losing it all

As the founder, you’re drawn to Strategy A: you get a life-changing financial return, you get to add “had a successful startup that was acquired” to your resume, and you might get to learn something interesting at the acquiring company. (Well, maybe.)

The VC firm will always pick Case B, because that’s what the model relies on.

The market also (sorta) requires it

Venture-backed outcomes are bimodal.

If you continue to grow, you eventually generate free cash flow, and your business has succeeded. If growth stagnates, the value of the business rapidly approaches zero, and the business either goes bankrupt or is sold for parts, because no one wants to fund a business that isn’t growing.

This is of course not true with a lifestyle business—your dentist’s practice won’t disappear if they can’t find exponential growth—but it is true for large-scale technology startups. In venture-land, growth rate matters much more than anything else, and you’re either growing well or you’re not. There’s no middle ground.

If you can’t hit growth escape velocity (i.e. if you can’t end up becoming the rocketship), you inevitably turn into the crater.

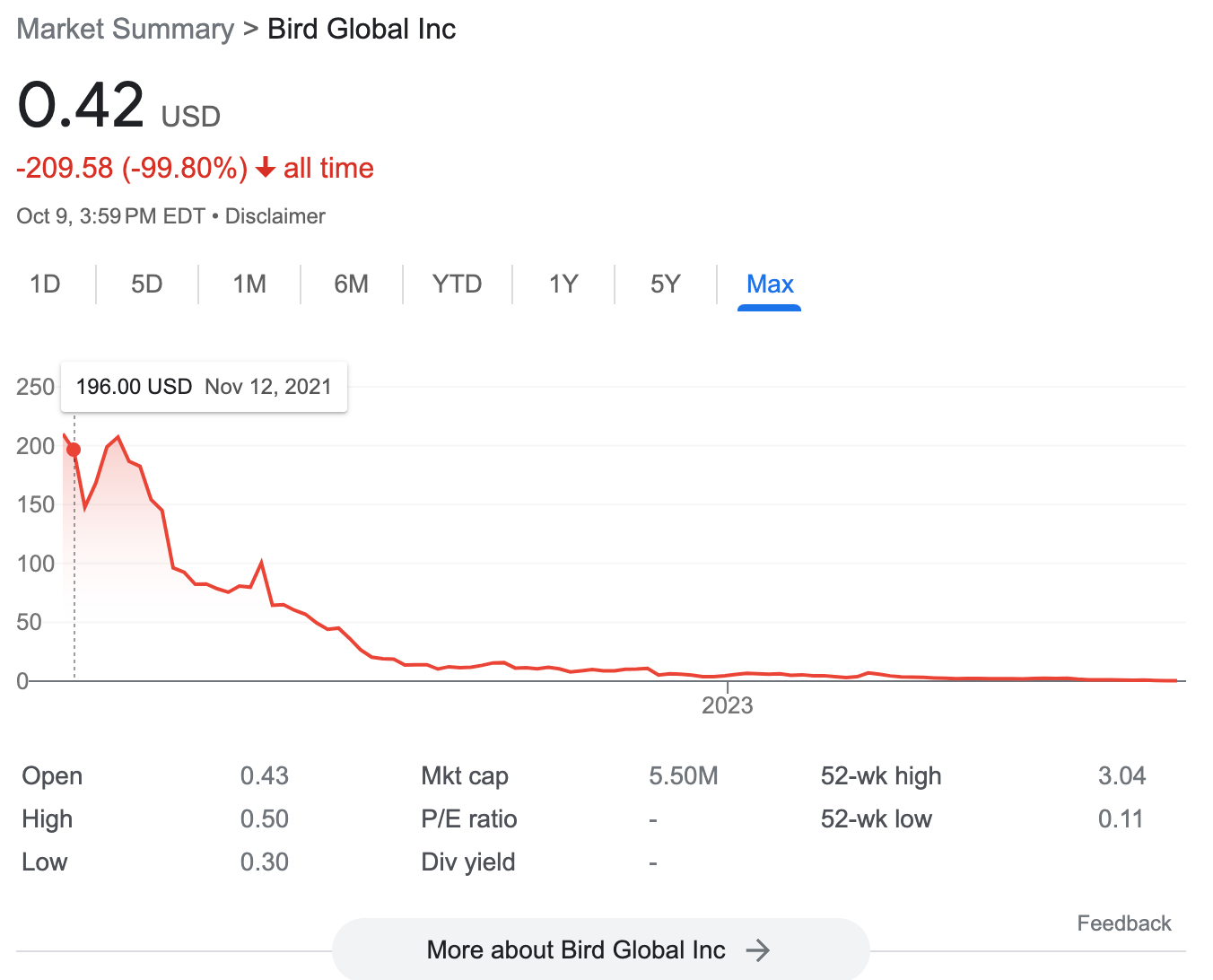

A very pronounced example from public markets:

What can you do about it?

First, consider whether venture capital is really right for your business. There’s no “right” way to fund a company, and VC is the wrong choice for many businesses.

If it is, understand and accept that your interests in this particular case are potentially strongly misaligned with those of your investors—which is OK, if you’re going into it with eyes open.

Finally, take steps that allow you to further align these incentives. In particular:

If an opportunity exists for you to take a little money off the table, do so (typically around the Series C stage)

Make sure you’re paying yourself a reasonable amount (see Pilot’s founder salary report here) so that you’re not eating into your savings

If you know you have a robust-enough financial cushion, it’s less scary to take the big swings that the venture capital model requires.